— Welch’s Floating Opal —

by Meg Andrews

COPYRIGHT© 2010-2025 MEG ANDREWS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

I have vivid

childhood memories of looking through my mother’s jewelry box and being

transfixed by her floating opal earrings. Time seemed to stand still as I

turned them over and over to see their fascinating displays of color and motion.

Recently, after purchasing an enchanting double floating opal necklace, I found

myself transfixed once again. And I began to wonder: who had created such an

intriguing and unusual form of jewelry, and when was it first made? Little did

I know that finding the answers to those simple questions would take months of

research, and would lead to the discovery of a quite remarkable and nearly

forgotten story.

I have vivid

childhood memories of looking through my mother’s jewelry box and being

transfixed by her floating opal earrings. Time seemed to stand still as I

turned them over and over to see their fascinating displays of color and motion.

Recently, after purchasing an enchanting double floating opal necklace, I found

myself transfixed once again. And I began to wonder: who had created such an

intriguing and unusual form of jewelry, and when was it first made? Little did

I know that finding the answers to those simple questions would take months of

research, and would lead to the discovery of a quite remarkable and nearly

forgotten story.

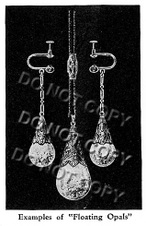

Appearing much

like a miniature snow globe, the floating opal is essentially comprised of

small chips of opal encased in a liquid-filled glass orb. Although floating opals are still manufactured today, the jewelry we recognize as vintage reached

the peak of its demand in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. Floating opal jewelry, in the form of pendant necklaces and earrings, was enormously popular during that period and was manufactured by innumerable companies. Surprisingly though, it was

decades earlier that the floating opal was first introduced. And

remarkably, its inventor was not a jeweler, but a 50-year-old,

Stanford-educated, patent-holding mechanical engineer. Beginning

in 1920, in a venture that would take him through the rest of his life, Horace

H. Welch patented, perfected, manufactured, and marketed his

invention—transforming it, and himself, along the way.

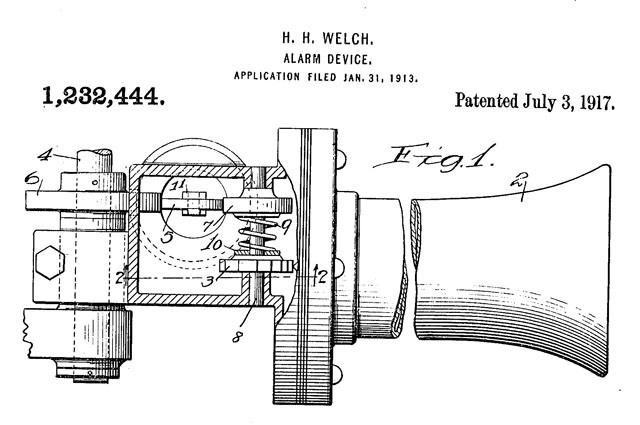

Horace H. Welch: Mechanical Engineer/Inventor

One has to wonder

what would prompt a man, whose previous patents included carburetors,

speedometers, fuel indicators, an early car alarm, and a mechanical pencil, to

invent and patent a process for manufacturing jewelry. Was it a mid-life

crisis? Was it a woman? The truth is that we may never know. What is known is

that within two years of receiving his first patent for what would become the

floating opal, Horace Welch left a seemingly successful career in Chicago and moved to

New York City to begin manufacturing and selling his “Gem.”

Horace Herbert

Welch was born in 1871, the second son of a country doctor, in La Cygne,

Kansas. Census data show the family living in Kansas through the year 1885, but by 1900, much of his family had moved to Los Angeles, California. Within that time frame, Horace attended Harvard University for a year (1892-93) and graduated from Leland

Stanford Junior University (1897) with an A.B. degree in physics. Little is

known of him from that time until August of 1910, when at the age of 39, he

filed for his first patent. In that application for the patent of a ”Speed Indicator,” Welch acted as assignor to the Stewart-Warner Speedometer Corporation of Chicago. In the following years

through 1920, Welch applied for no less than thirteen1 mechanical and electrical

patents from various locations including Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and

Milwaukee.

Horace Herbert

Welch was born in 1871, the second son of a country doctor, in La Cygne,

Kansas. Census data show the family living in Kansas through the year 1885, but by 1900, much of his family had moved to Los Angeles, California. Within that time frame, Horace attended Harvard University for a year (1892-93) and graduated from Leland

Stanford Junior University (1897) with an A.B. degree in physics. Little is

known of him from that time until August of 1910, when at the age of 39, he

filed for his first patent. In that application for the patent of a ”Speed Indicator,” Welch acted as assignor to the Stewart-Warner Speedometer Corporation of Chicago. In the following years

through 1920, Welch applied for no less than thirteen1 mechanical and electrical

patents from various locations including Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and

Milwaukee.

That Horace was an

intelligent man is without question. One has only to read the multitudinous

pages of his 24 known patents to observe his quite brilliant and meticulous

mind. His dramatic pen style revealed also a great capacity for showmanship and

promotion — qualities that would serve him well in the jewelry industry. Because

he never married and lived so far away from his California relatives, living

family members know little of him but do report that the family considered him eccentric.

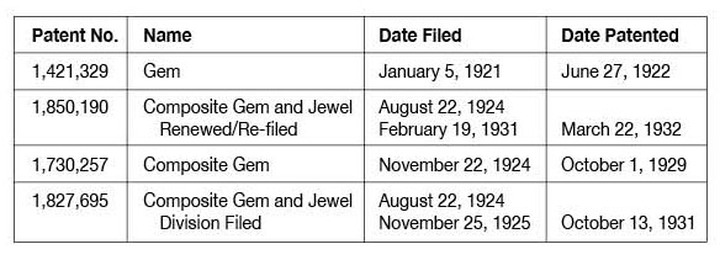

Welch’s Patents:

The Development of The Floating Opal

For an accurate timeline of the development of “The Floating Opal,” it is best to look at the patents2 in the order that they were filed rather than when they were

issued. (See chart.) Welch’s first application for what would become the floating opal was

filed in January of 1921, and was entitled simply …“Gem.” It was approved

swiftly by U.S. patent standards in June of 1922 and given the number 1,421,329.

For an accurate timeline of the development of “The Floating Opal,” it is best to look at the patents2 in the order that they were filed rather than when they were

issued. (See chart.) Welch’s first application for what would become the floating opal was

filed in January of 1921, and was entitled simply …“Gem.” It was approved

swiftly by U.S. patent standards in June of 1922 and given the number 1,421,329.

The patent was very

general in nature and consisted of a single page of drawings and only two and a half

pages of description. In flowery language, Welch wrote that his invention

pertained “to a novel and pleasing type of gem or jewel adapted for many and

varied uses, particularly in the production of jewelry.” He mentioned opals

only in passing, and described instead that the shell could be filled loosely

with “the well-known sparkling granular ‘metallics’ of the trade,

or...crumpled pieces of gold leaf, tinsel or the like.” He stated that the

jewelry could be made with or without liquid using a single loose gem or a

number of display elements, and he included the rather impractical examples of

a ring and a strand of beads.

Even before that

first patent was granted, a May 1922 publication of The Stanford Illustrated Review

noted its alumnus as follows:

’97-Horace H. Welch, mechanical engineer, originally of Los

Angeles, and for the last few years of Chicago,

has invented and patented more

than twenty mechanical devices for electrical and other machinery.

One of his

latest inventions is a heavy colorless liquid in a tiny glass globe holding

minute bits of

colorful opal to be used for cheap rings and necklace

pendants.

There, for the first time, was the commitment to opals and necklace pendants. Sometime in the

year and a half between his patent application and that publication, Horace’s

tinsel-filled novelty had made the leap toward becoming a floating opal. Just

how he came to conclude that opal fragments should be the display elements is

hard to guess. It is likely that he was searching for something attractive yet inexpensive, as his goal was to produce a new and cheaper form of “high-grade” jewelry. The opal, with its history of being both prized and shunned, was

enjoying a new wave of popularity, and owing to its fragility, fragments were “common and of low cost.” Whatever it was that led Horace to the opal, his

subsequent applications show a definite shift in focus and a significant

concentration on displaying the opal’s colors most advantageously.

Apparently, there were initial production problems related to the gem’s fragility and its tendency to

break. In August and November of 1924, Welch filed his second and third patent

applications, in which he detailed the necessary improvements and added many very specific enhancements. In contrast to the first, these applications were quite

voluminous and present strong evidence that Welch had growing concerns about

protecting his invention. Although he offered a multitude of variables, several

essential elements emerged that came to comprise the floating opal as we know

it today.

Most importantly

and in simple form, those elements were:

1.

The

introduction of the bubble within the globe as a necessary air space that

allowed for the expansion of the liquid without fracturing the glass housing.

2.

The

method for constructing a second smaller chamber above the main display chamber

that allowed the liquid to expand, and

served to trap the bubble where it could be hidden. (Ever the engineer, Welch

referred to this two-chamber model as “double globular.”)

3.

The

introduction of glycerin as the liquid suspension. While Welch stated that a

variety of liquids could be used, he concluded that glycerin enhanced the

brilliancy of the opals, provided the ideal viscosity for motion, and acted as a preservative of the chips.

(Research confirms that glycerin was and is the industry standard.)

4.

The

preference for using the relatively new invention3 of Pyrex® glass as

the housing. Not only did Pyrex® provide a stronger housing, but

when used in combination with glycerin (which has a similarly high refractive

index), the two virtually disappeared to produce the “illusion of a unitary

large opal.”

Welch’s

second and third applications did not enjoy the same swift approval as his

first. (One would take almost 8 years and the other nearly six.) Apparently at the request of the Patent Office, Welch filed yet another

application in November of 1925. That fourth application was a division of his

still pending second application. (A division is usually requested when an

application contains too many ideas.) Other patent struggles were revealed in a

1929 U.S. Court of Claims ruling, which disclosed that the Patent Office had rejected

some of Welch’s claims and denied his subsequent appeals. That 1929 ruling

reversed the Patent Office’s denial and in the following three years, Welch’s

pending applications were finally patented.

H. H.

Welch: Jeweler

Eight

years after his first floating opal patent, 1930 census data showed Welch

living in Manhattan. At age 59, his occupation was listed as “jeweler.” His

transformation was complete. He had chucked his engineering career to

wholeheartedly embrace his jewel invention. Somehow, even with a deepening

depression and several patents still pending, he had managed to successfully

produce, promote and sell the floating opal.

Eight

years after his first floating opal patent, 1930 census data showed Welch

living in Manhattan. At age 59, his occupation was listed as “jeweler.” His

transformation was complete. He had chucked his engineering career to

wholeheartedly embrace his jewel invention. Somehow, even with a deepening

depression and several patents still pending, he had managed to successfully

produce, promote and sell the floating opal.

After his 1922 patent, Welch wasted no time getting to the production and sale of his floating opal jewelry, and all indications are that it was a hit. In the spring of 1924, newspaper fashion articles and display ads appeared heralding floating opals as a fascinating new mode. In 1926, jewelry store display ads were touting the floating opal as “a gem worthy the treasure chest of a queen.”

By all

accounts, the H. H. Welch Company4 was a modest operation with a small manufacturing facility. It is likely, in fact, that

Welch produced many of the floating opals himself. He apparently enjoyed success

selling his invention to jewelry stores nationwide and he continued to promote

it as a “new jewel” well into the 1930s. His final floating opal patents were

issued in 1931 and 1932, and there was another big promotional push at that time including a brief article in Scientific American magazine.

Probably as a result of the Great Depression, demand seems to have dampened by

the late 1930s, and the ads and articles appeared less frequently.

Welch

continued to produce floating opals until his unexpected death in 1947. The

1940s had not been without challenge. As early as 1943, Coro began advertising

a line of “genuine floating opals” and Welch did what any patent holder would do: he sued for patent infringement.

Sadly, the suit was not settled until 1951, and Horace did not live to see it.

After his death, his brother and nephew spent months in New York working to

settle the estate. They sold the business to Robert Rose and as late as 1966,

H. H. Welch, Inc. was still listed in the Jeweler’s

Circular Keystone as a supplier of floating opal jewelry.

In 1949,

twenty-seven years after the floating opal’s first appearance, Welch’s final

patent expired, leaving the door open to any and all manufacturers. And they

did not hesitate to step through it. Newer technology allowed faster production

and floating opals proliferated the market. No longer limited to jewelry

stores, floating opals were widely available and sold in department stores

nationwide. Perhaps remembering their mothers’ floating opals, women embraced

this “new” jewel with zeal. Floating opal jewelry became a popular bridal

accessory, and many wedding announcements included statements like, “the

bride’s only jewelry was a floating opal pendant,” or “the bride wore a pair of

floating opal earrings, a gift from the groom.”

Although

Horace Welch had no way of knowing that his floating opal would continue to be

appreciated, coveted and manufactured into the 21st century, I am certain that

he knew it was something quite extraordinary. Using his scientific knowledge,

keen mechanical mind and dogged persistence, he combined glass, glycerin, and

some broken opals to construct an enchanting new jewel. The Floating Opal was

his masterpiece and its creation showed that this eccentric engineer had the

heart of an artist.

Identifying,

Dating, and Assessing Welch’s Floating Opals

The Cap Markings

Welch’s

floating opal pendants* can be identified and dated by the markings on their

decorative caps. (Necklace

chains should not be used for identification purposes as they were often

supplied by the retailer.) All

of Welch’s early pendants were set in fine gold and the gold content (14K or

18K) is marked on the cap. The early caps are also marked with patent

information and that is how they can be dated.

Welch’s

floating opal pendants* can be identified and dated by the markings on their

decorative caps. (Necklace

chains should not be used for identification purposes as they were often

supplied by the retailer.) All

of Welch’s early pendants were set in fine gold and the gold content (14K or

18K) is marked on the cap. The early caps are also marked with patent

information and that is how they can be dated.

-

Caps marked “PAT. 6.27.22” date from 1922 to 1929. These are the

earliest floating opals.

-

Caps marked “PATS. PEND.” were probably manufactured between 1929 (after the U.S. Court of Claims ruling) and

1931. Welch would have used this mark as he waited for his second, third and fourth patents.

-

Caps marked “PAT. 10.13.31,” refer to Welch's patent 1,827,695 and were made after October 13, 1931 and into the 1930s.

-

Caps marked simply “PAT.” most likely date after the final patent date

of March 22, 1932.

It is

very probable that Welch’s floating opals continued to be marked with some form

of patent information until 1949, when the last patent expired.

There are other Welch’s floating opals with cap styles different than those I have shown. However, all that I have seen have been marked in one of the ways listed above.

*I have

never seen a Welch floating opal ring although jewelry store ads indicate that they

were manufactured through the early 1930s. I assume that they too, would have

been marked with patent information.

Another Surprise—Invisible Solids

In

Welch’s third patent application, I was surprised to discover that he

recommended adding “invisible solid parts,” in the form of bits of Pyrex®

glass, to the opal chips. He stated that this addition decreased the cost and

that because the parts essentially became invisible, they spaced the gems and

improved their beauty by “increasing the number of reflecting gem surfaces.” Close

examination does confirm “invisible” bits of Pyrex® glass floating among the

opals. I am hopeful that invisible solids were exclusive to Welch’s jewelry and

will provide an additional way to identify his pieces. (I do not see any invisible

solids in my mother’s floating opal earrings, which were made by Opalite.)

A Note About the Bubble

To many

eyes, the bubble is a flaw and the truth is that Welch felt the same way. With

his “double globular” design, Welch was able to hide the bubble under the

pendant cap (he used another method for rings). In addition, he attempted to

make the passage between the two chambers narrow enough to keep the bubble in

top chamber and thus prevent “the evil appearance of the otherwise useful air

space.”

To many

eyes, the bubble is a flaw and the truth is that Welch felt the same way. With

his “double globular” design, Welch was able to hide the bubble under the

pendant cap (he used another method for rings). In addition, he attempted to

make the passage between the two chambers narrow enough to keep the bubble in

top chamber and thus prevent “the evil appearance of the otherwise useful air

space.”

Current

belief is that any bubble in a floating opal reflects damage and that it

detracts from the value. While a very large bubble is an indication of

leakage and should be avoided, I would argue that in these early pieces, the

theory of trapping the bubble was probably much easier than the actual

practice. As handmade jewelry, floating opals suffer the human touch and are all

the sweeter for it. Although attempts were made to keep it from sight, many a

bubble has escaped its chamber and can be seen when a pendant is lying prone or

held inverted. It is important to remember too that some of Welch’s pendants are close to

90 years old and the fact that they have survived at all should weigh heavily

in their favor.

1 There is a good deal of incongruity regarding the number of patents Welch received. I found a total of 24, issued to our Horace Welch between 1910 and 1935, but there could be more. Surprisingly, there is more than one patent-holding Horace Welch. I was able to discount the others, including Horace Welch of Selma, Alabama, and Horace H. Welch of Earlville, New York, by using census data.

2 The article in Scientific American magazine states that Welch is the inventor of the floating opal and "possesses five patents covering it." I could only find four floating opal patents issued to Mr. Welch. He did re-file his still pending second application in February of 1931, so it's possible that he considered it the fifth patent.

3 Pyrex®, a borosilicate glass, was a relatively new product, having been introduced to America by Corning Glass Works in 1915.

4 According to Dorothy Rainwater's book, American Jewelry Manufacturers, H. H. Welch of New York, New York, is referenced in the 1931 Keystone, and the 1943 Jewelers' Circular Keystone as the manufacturer and patentee of "The Floating Opal."

CLICK HERE FOR PAGE TWO: A FLOATING OPAL QUICK GUIDE

This article, in condensed form, was originally published in

the Winter 2010 Costume Jewelry Collectors International quarterly magazine

(Volume 1, Issue 4).

Special thanks to Horace Welch's great nieces, Nancy and

Laurel Ann, for their help in piecing together this story. Thanks also to Marc

Stonberg (Opalite, Inc.) for sharing his knowledge of the

floating opal industry.

Floating Opal jewelry photography by Gary Simmons.

RESOURCES:

Google Patents.

www.google.com/patents

Ancestry.com. www.ancestry.com

Rainwater, Dorothy T., American

Jewelry Manufacturers, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 1988.

The Keystone Jewelry

Trade Mark Book. The Keystone Publishing Company, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

1934.

"An ‘Assembled' Jewel,"

Scientific American, Vol. 147, No. 4, Scientific American Publishing

Company, New York, New York, 1932.